Emigrants, America and An Unsuccessful

Revolution in Germany: 1848/49

The complete text will be fit in here. The original text is contained in the Landesbibliothek (state library) at Oldenburg.

As early as on 4 April 1848 German-Americans agreed on a call for solidarity which was published in Sunday´s Newspaper in Vechta, a catholic region to the south of Oldenburg, on 21 May 1848. This appeal included the promise that successful revolutionists would be given a flag of liberty; however, it seems that the flag remained with the "Queen of the West", i.e. "over the Rhine" as the German quarter beyond the dirty canal was called.

An "Address of the citizens of New York" of 20 April 1848 was delivered to the National Assembly of Frankfurt on the Main at the Paul`s Church on 6 June 1848 (Franz Wigand (ed.): Reden für die deutsche Nation 1848/49 [Addresses to the German Nation 1848/49]. Stenographischer Bericht über die Verhandlungen der Deutschen Constituierenden Nationalversammlung zu Frankfurt am Main, [Shorthand report on the negotiations of the German Constitutional National Assembly of Frankfurt on the Main], Bd. 1, Frankfurt: Sauerländer 1848, p. 162f, Nachdruck München: Moos & Partner 1988).

On 7 December 1848 the National Assembly decided that the right to emigrate is a constitutional right (Wigard, Bd. 5, p. 3897):

All this has become rubbish: a revolution, which once it at first bloodily utterly fails and also hesitates and resignedly is given up. A committed nationalism before the unification remained alive; the founding of the empire in 1871 satisfied many revolutionaries in America. Philipp Veit had already concealed the "Germania" in St. Paul's Church with the organ and ruled the church space, but so many speakers all the way from the left to the right.

Many revolutionists fled or emigrated to the USA. Sympathizers have also left. Jakob Julius Schlickum from Westphalia, for instance, was one of them. (Hans Dahlmanns, Voerde am Niederrhein). The teacher of agriculture (1825-1863) who had an academic training said goodbye in a very emotional way in June 1849:

Many of the emigrants were welcomed by the German-Americans in a very unfriendly way: Some of the insults were printed in "Der Oldenburgische Volksfreund" on 3 April 1850, long after it had turned out that the revolution and the negotiations in the Paul´s Church had failed:

The church paper of the old-Lutheran Missouri synod (St. Louis) reported and commented on the revolution for 5 years:

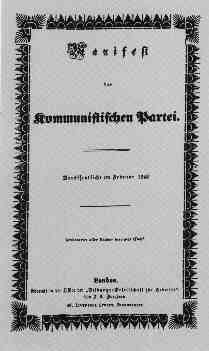

In February 1848 the 'Communist Manifest' of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels was published. .

'Society' was the governing idea of civil enlightenment - and its egalitarian radicalization became apparent in the Communist Manifest: 'an association in which the individual development of any person provides the basis for the development of all'," (Matthias Geffrath, in: Die Zeit, 5 February 1998. These were the dreams of mankind that had come to an end in bloodshed and that had been given up hesitantly and with resignation.

The Frankfurt physician Heinrich Hoffmann (a liberal-conservative revolutionist) wrote under the name of "Peter Struwwel" (Peter Shockhead) a "Little Handbook for disturbers or 'A short introduction into how to become popular in a few days' (Leipzig: Gustav Meyer publishing house). In an attached "Dictionary of popular catchwords" he explained to left republicans what the term 'republic' means:

For 70 years Germans could only dream of democracy and a republic.

| [HOME] | [GERMAN] | [DATA PROTECTION] |

| Research Center German Emigrants in the USA: DAUSA * Prof.(pens.) Dr. Antonius Holtmann Brüderstraße 21 a -26188 Edewecht - Friedrichsfehn *Kontakt: antonius.holtmann@ewetel.net | ||